After a busy morning at the Guildhall School of Music Mila and I decided to visit the ‘Empire of the Sikhs’ exhibition at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS.

It’s described by the organisers as “featuring a glittering collection of stunning objects and works of art that reveal the remarkable story of the Sikh Empire (1799-1849), and the European and American adventurers who served it, an empire that spanned much of modern day Pakistan and northwest India.

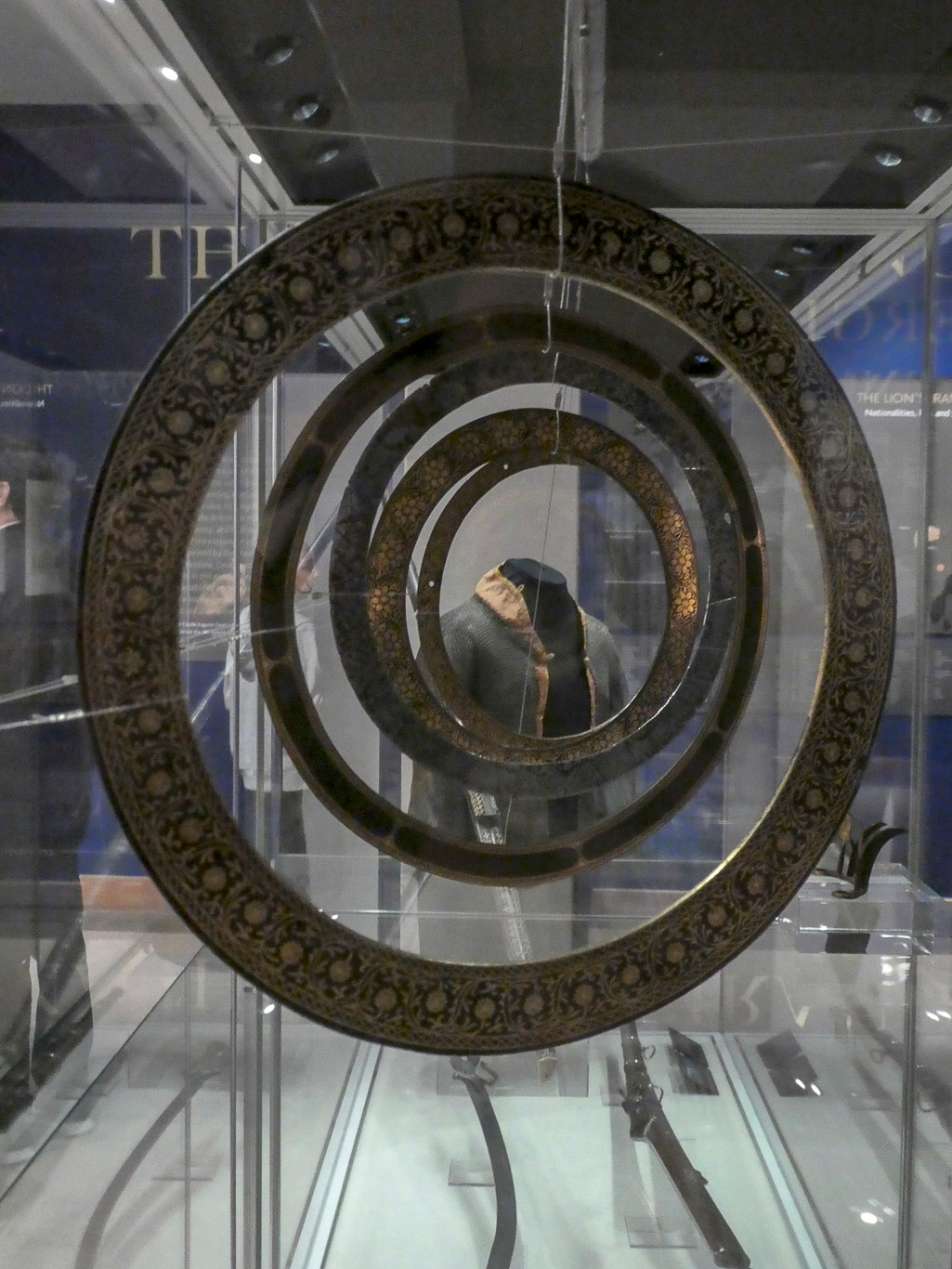

This beautifully intricate screen marked the entrance to the exhibition.

Not knowing the history very well myself I’ve included much of the information provided by the exhibition.

Not knowing the history very well myself I’ve included much of the information provided by the exhibition.

Despite it being quite a small exhibition it is well worth a visit. It shows what’s described as ‘A Golden Age of Empire’ with the forty year reign of the Sikh ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, known as the ‘Lion of the Punjab’ and how he created a fabulously rich empire over vast areas of territory from the Khyber Pass across Punjab and Kashmir to the Tibet border. With this empire came great wealth and the development of a powerful army.

Being so powerful and wealthy, the Sikh ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, could rise above the usual prejudices allowing those of any faith to hold senior posts as advisors, administrators, courtiers, generals and governors. This policy of meritocracy included nearly a hundred European and American adventurers and military men known as ‘firangis’ meaning foreigners – who helped modernise his army and administer the vast kingdom.

The SOAS website tells us that he was ‘a trusted ally of the British but also a potentially formidable opponent. The inevitable clash with the British came in the form of two bitterly fought Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-46, 1848-49) in which the British finally achieved victory despite coming within hours of surrender through treachery resulting in the territory, treasury and fighting men coming under British control . . . So with this in mind let’s find out what the exhibition has in store for us . . .

INTRODUCTION

As revolutionary winds swept across France and America in the late 1700s, the ancient region of Punjab – the ‘Land of Five Rivers’ that today spans Pakistan and India – was witness to a people’s movement that changed the course of history on the subcontinent and, ultimately, strengthened Britain’s role as a world power.

The central players were the Sikhs from Punjab, the northern gateway into the Indian subcontinent. These revolutionaries were disciples of the ten mystics beginning with Guru Nanak (1469-1539) who travelled great distances spreading a unifying message of Oneness. His teachings focused on the importance of humanity, devotion and humility confronting hypocrisy, tyranny and oppression. It was under the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708) that Sikhs underwent a transformation ‘from sparrows into hawks’.

Fostering a martial culture, the Guru prophesied kingship, which propelled his daring Sikh warriors onto a path of sovereignty.

With an unflinching self-belief and hard-hitting guerrilla tactics, the Sikhs organised under a multitude of independent confederacies to take on the most powerful empires in the region. While the American Revolution (1765-83) was running its course, the Sikhs wrested control of Lahore from the Afghans and penetrated the heart of Mughal Delhi’s fabled Red Fort to occupy their mighty capital for eight months.

Although they had succeeded in bringing about an unprecedented era of peace in a region wracked for centuries by savage invasions, religious fanaticism and social injustice, the Sikhs lacked unity. One among them, an improbable ten year old boy named Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), scarred and blinded in one eye from smallpox, was destined to consolidate their conquests and go on to found an empire, encompassing the Mughal provinces of Lahore, Multan and Kashmir, and beyond into Ladakh in the north and Afghan territories to the east.

In recognition of his supremacy, Ranjit Singh would become the ‘Maharaja’ or Great King, and hailed as the Lion of Punjab for his remarkable achievements. This exhibition explores not only his life and legacy, but also introduces the Americans and Europeans who helped him develop a formidable, multi-cultural empire that kept at bay the threat of British invasion during his reign.

Ultimately, in the bloody clash of empires that followed his death, the British finally took possession of what became one of the most valuable jewels in the imperial crown, the Empire of the Sikhs.

One of the exhibition’s first exhibits is a Sikh gun-howitzer from Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s artillery battery and is one of a pair of Sikh guns that were presented to General Sir Hugh Gough (commander-in-chief of the British forces) following the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9).

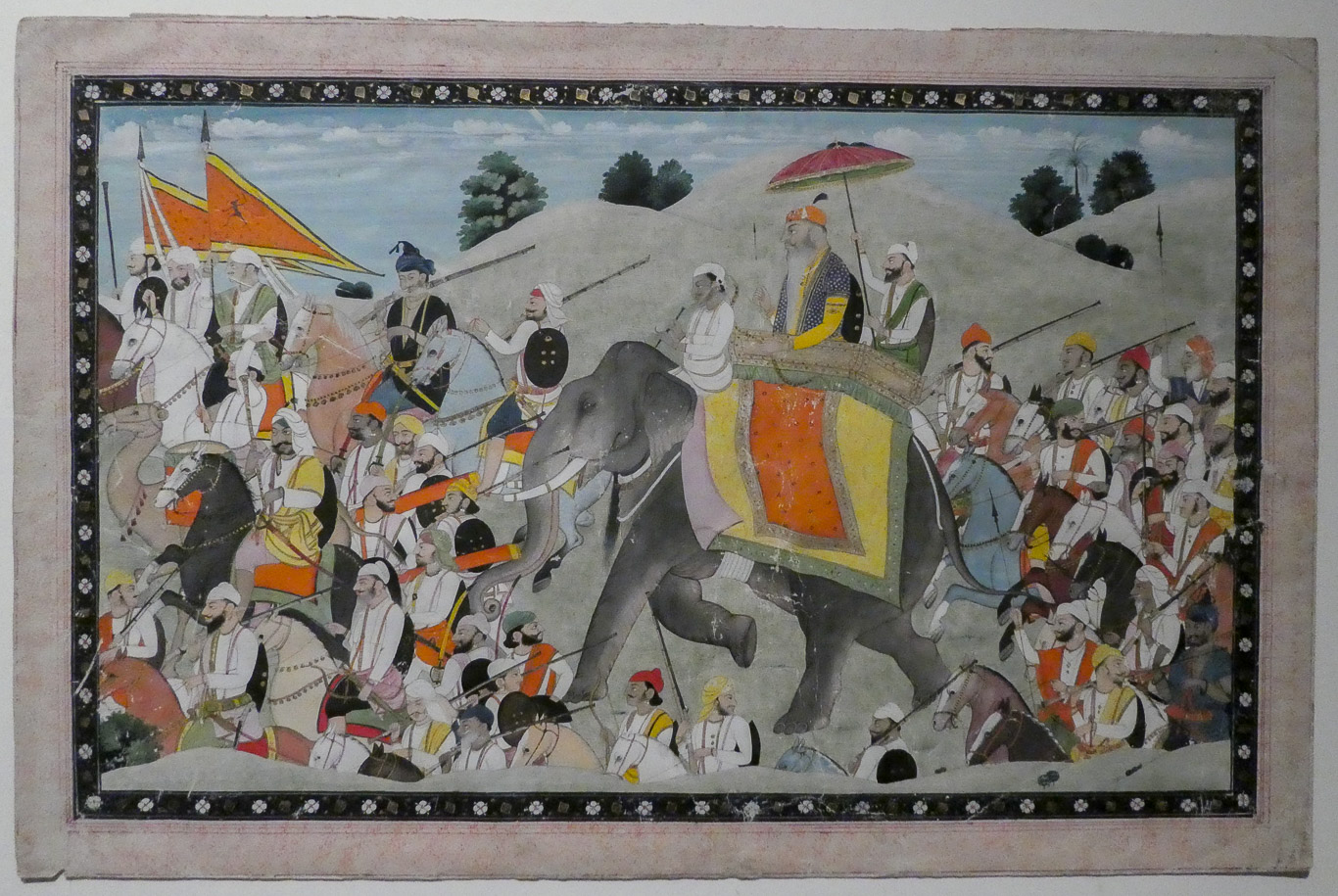

General Hari Singh Nalwa with his retinue

General Hari Singh was a senior commander of the Sikh army and the one to whom the Maharaja was most attached. He was employed to command all expeditions of exceptional difficulty, helping to extend the Sikh Empire almost up to the Khyber Pass.

Here he leads his cavalcade of irregular cavalrymen from his charging elephant. From collecting revenue and suppressing criminality, to constructing forts and tackling the jihadis threat, he became the firm favourite of the Sikh soldiery. Afghan mothers even used his name to scare their children into doing as they were told.

Alkali-Nihang Sikh warrior and his wife

Major Leech, a British political agent, observed in the 1840s how the wives of the Alkali-Nihang Sikhs ‘are also armed like the men, and are said to be expert horsemen’. They spoke like their male counterparts, adopted their mannerisms and bore similar names.

Adventurers, Mercenaries and Medicine Men

Notable among the firangis – foreigners – were two American mercenaries whose exploits inspired Rudyard Kipling’s ‘The Man Who Would Be King’.

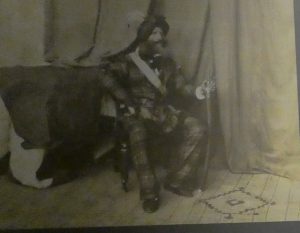

Alexander Gardner was the most extraordinary of Ranjit Singh’s foreign contingent and reminds us of the diversity of people in the Sikh Empire at its height. Before arriving at Lahore Gardner had spent 13 years venturing deep into regions previously unchartered by westerners, roaming the deserts of Central Asia in various disguises before riding round the world’s most fearsome knot of mountains, among them the Great Himalaya range.

Alexander Gardner was the most extraordinary of Ranjit Singh’s foreign contingent and reminds us of the diversity of people in the Sikh Empire at its height. Before arriving at Lahore Gardner had spent 13 years venturing deep into regions previously unchartered by westerners, roaming the deserts of Central Asia in various disguises before riding round the world’s most fearsome knot of mountains, among them the Great Himalaya range.

Almost as famous was Josiah Harlan who led the life of a chancer. After first passing himself off as a surgeon with the East India Company he headed for Afghanistan with ambitions of kingship. He eventually ended up serving as a governor under the Sikhs but fell out with Ranjit Singh for allegedly minting counterfeit coins.

More respected was the Austro- Hungarian doctor, Johann Honigberger, who became the maharaja’s trusted court physician. Like Gardner and Harlan, memoirs of his eastern adventures were published in the late 19th century to satisfy the curiosity of western readers.

Other exhibits

Sikh turban-helmet (taup)

This elegant gold-decorated helmet has been carefully forged to accommodate the tightly-bound Sikh turban complete with top knot. It was exclusively worn by the Sikh Dragoons of the Fauj-i-Khas.

A rare Sikh tiger claw

This menacing weapon is probably the only implement of war that can be said to be an invention of the Sikhs. It is comprised of five forward-projecting blades and two double-edged daggers attached to a curved bar, specially designed to be fastened upon a quoit in the turbans of Sikh warriors.

Sikh quoits (chakkars)

This ancient projectile weapon traditionally associated with the Hindu god Vishnu and used by Shivite ascetics (followers of the Hindu god, Shiva) became closely associated with the Sikhs after Guru Gobind Singh innovated its use as a highly effective shock weapon in close quarters. As Sikh rule flourished in the 18th century onwards, these quoits became increasingly more elaborately decorated.

Three archer’s thumb rings

In Indian archery, the thumb was normally hooked around the bowstring rather than using a number of fingers as in the normal European method. By using a thumb ring, the pressure was significantly relieved.

Settling down

The binding conditions of service under Sikh rule included growing a beard, abstaining from eating beef and smoking in public and promising to remain loyal to the Sikh empire, even if it meant going to war against one’s own countrymen. Another stipulation of service was to marry locally.

Allard, a General in Ranjit Singh’s army, was the first to wed in 1826. Colonel Mouton‘s intrepid Kashmiri wife helped save him from mutinous troops while Gardner married a Rajput lady from the household of Raja Dhylan Singh and through her gathered a good deal of intelligence material from the local bazaars. An exception was General Ventura who married an Armenian lady residing in British-India, though he also maintained a harem of concubines.

With high rank came ample pay, often part-paid in expensive Kashmiri shawls and the luxurious trappings of office in grand settings. While Allard and Ventura built themselves an imposing classical dwelling in the grounds of the tomb of Anarkali, Court set up home in the grounds of the tomb of a Mughal courtier. Some like Gardner maintained a large household establishment with twenty servants.

Several officers such as Allard, Court and Honigberger later resettled their Punjabi families back in Europe.

Art patronage and discoveries

Many of Ranjit Singh’s foreign contingent developed an active interest in the culture, history and archaeology of the empire. The firangis’ curiosity about their adopted home led them to play a pioneering role in unearthing the ancient history of the region. Their industrious efforts helped the ancient cultures of the Indus, Punjab and Afghanistan gain international recognition and appreciation.

Photograph below:

1. Scene of the Golden Temple, the basin and a party from the village of Amritsar in the kingdom of Lahore – this is the earliest image of the Sikhs’ most famous shrine, the Sri Harmandir Sahib (“abode of God”) – popularly known as the Golden Temple – to have been published in Europe.

2. The Rat and the Elephant from Fontaine’s Fables – the vivid painting of a Sikh Queen on an elephant illustrates a fable found in a specially printed copy of Jean de la Fontaine’s Fables.

3. Rare portrait cameo of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan – this tiny carved cameo of the Mughal emperor who created the Taj Mahal was gifted by General Court to Isabella Fane.

4a-d. Murals in General Avitabile’s home in Wazirabad – A rich diversity of themes is reflected in these murals which are typical of those that once adorned residences, palaces and places of worship across the Sikh Empire.

5. View of Govindgarh Fort – Situated a quarter of a mile outside Amritsa, Ranjit Singh began to build this fort on the site of an older fortification in 1807 to protect the city.

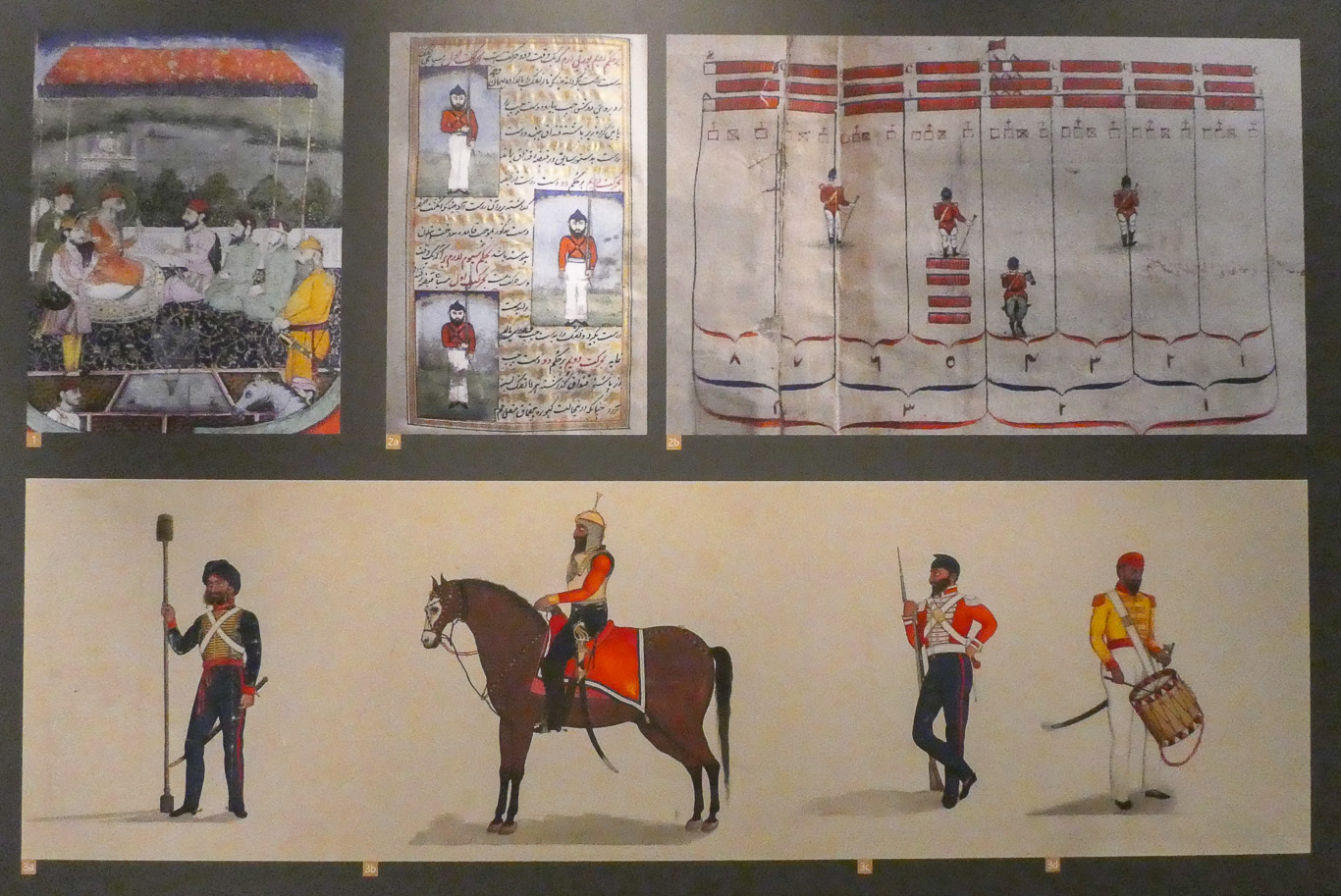

The picture below shows Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Court. The Sikh ruler is shown in court with two firangi Generals, Ventura and Allard. The manuscript is a Manuscript of Military Manoeuvres (while raising the first two units of the Fauj-I-Khas in 1822 Allard and Ventura translated two French Military Manuals into Persian). The lower picture is of troops of the French inspired Fauj-I-Khas. These figures show the European inspired uniforms of the regular artillery, cavalry and infantry.

There were many amazing exhibits including the Armlet for the Koh-I-Noor Diamond and a broach depicting the Maharani Jind Kaur and another of her earrings to name just a few!

END OF EMPIRE

Anglo-Sikh Wars and Annexation of Punjab

Within a few years of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, deadly court intrigues led to the murders of three successors to the throne along with three chief ministers.

This period of anarchy was compounded by a restless army led by military councils that assumed the role of king-maker. The final claimant to the throne was the five year old Duleep Singh. His mother and regent, Maharani Jind Kaur, along with her advisers Lal Singh and Tej Singh, instigated the army into a confrontation with the British East India Company, which had been moving troops and equipment to the border.

In what were some of the bloodiest battles the British had ever fought in the subcontinent, the forces of the Sikh Empire were defeated in the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-46) largely as a result of the treachery of its leaders, Lal Singh and Tej Singh. As Company officials effectively took control of the state, simmering discontent let to the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49), which proved decisive – in 1849, the territories of the Sikh Empire were annexed to British India.

Maharaja Duleep Singh and Lord Dalhousie

This rare double-portrait of the last Sikh ruler of Lahore and the governor-general of British India who deprived him of his birthright provides a unique visual record of the two most pivotal players in 19th century Punjab’s history.

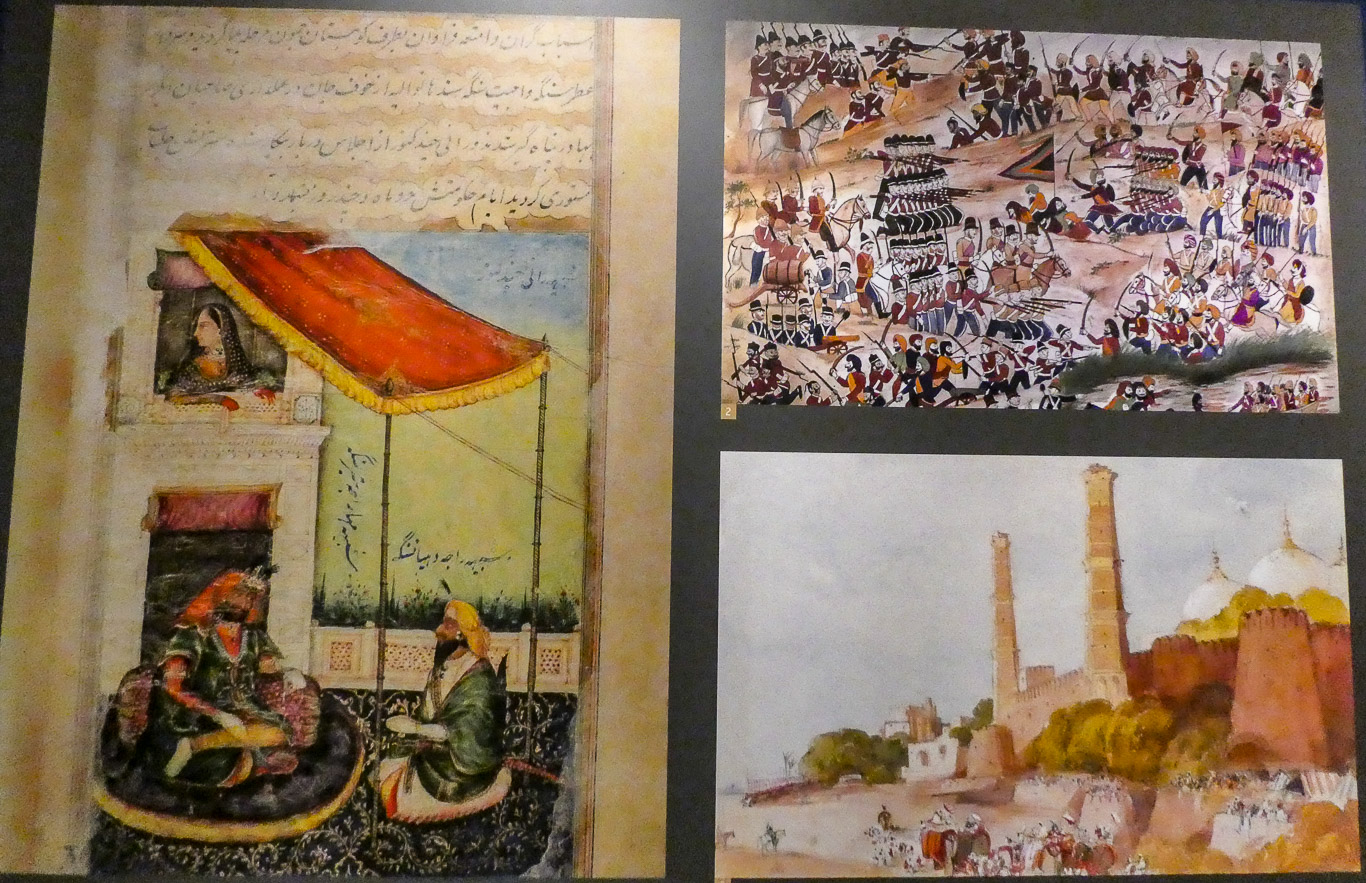

Maharani Chand Kaur looks down upon Maharaja Sher Singh as he converses with Raja Dhylan Singh

The bloodbath that followed the death of Ranjit Singh claimed the life of his eldest son, Maharaja Kharak Singh (1801-1840). While Kharak Singh’s son and successor, Nau Nihal Singh (1821-1840), died under suspicious circumstances on the day of his father’s cremation, his wife, Maharani Chand Kaur (1802-1842), was stoned to death by her maid servants. The order was probably given by Sher Singh (1807-1843), who became the fourth maharaja in as many years. Yet he and his chief minister Dhylan Singh fared no better – both were assassinated on the same day. Next to ascend to the throne was an infant son th the Lion of Punjab, Duleep Singh (1838-1893).

The Battle of Sobraon

The last battle of the first Anglo-Sikh War has been shown in this rare artwork by an anonymous Punjabi artist.

Having been forced to retreat to the southern bank of the River Satluj, the Sikh army had hastily constructed a formidable defensive earthworks two and a half miles long near the village of Sobraon. Behind these entrenchments built by a Spanish engineer still in the service of the Sikh Empire, were positioned some 25,000 men and 70 guns. As the battle grew nearer, demands for reinforcements were only partially met by the Lahore Court and several leading generals and courtiers on the Sikh side conspired to delay its start, allowing British reinforcements and heavy guns to be put in place.

The British opened the attack on 10th February 1846 with a heavy artillery bombardment, to which the Sikh guns responded in kind. With their ammunition supplies running low, the British infantry rushed the trenches, driving the gallant but leaderless Sikh forces towards the river. A pontoon bridge constructed primarily for supplies also offered a means of strategic retreat but it was here that they were cruelly betrayed by their generals, Tej Singh and Lal Singh. Having already fled with their own men across the river, they sank a boat in the middle and effectively cut off the army’s route of retreat.

Of the estimated 10,000 Sikh, Muslim and Hindu soldiers of the Sikh forces who perished in the battle, most were drowned or blown away in the fearful slaughter that took place at the head of the pontoon bridge as they attempted to ford the river.

Entry of British forces into Lahore

The painting (bottom right of the three pictures above) captures the historic moment that Maharaja Duleep Singh entered his palace in Lahore accompanied by an escort of British troops after the fateful battle of Sobraon.

The few firangis who had fought under the banner of the Sikh Empire in the recent was were deported but the British. A similar fate awaited the boy-king, Duleep Singh. Within the space of a few years he would be separated from his mother, deposed and eventually exiled to England. At the age of eleven he was made to sign away all his possessions, including the priceless Koh-i-Noor diamond, which was presented to Queen Victoria in 1850.

Maharaja Sher Singh wearing the Koh-I-Noor diamond.

This vivid portrait of the maharaja shows him as master of both war and wealth and represents the Sikh Empire at its zenith.

Carving up of the Sikh Empire

Upon the conclusion of the first Anglo-Sikh War in 1846, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Kingdom was divided into three parts.

The vast majority of the territory was allowed to remain a sovereign state with Maharaja Duleep Singh at its head. However, the levers of power were placed firmly in the hands of a British resident who remained at Lahore with a small army. Other territory (Jalandhar Doab) was taken under the direct control of the British Government. Finally, as part of the post-war settlement and as a reward for his services in the recent conflict, the courtier Raja Gulab Singh, was effectively allowed to purchase vast, highly coveted territory in the region of Jammu and Kashmir.

Photograph below: Old Lahore today – This modern view of Lahore shows the Mausoleum of Maharaja Ranjit Singh built in 1849 against a backdrop of the 16th century Badshahi Mosque. (Photograph by Mobeen Ansari, Lahore, 2009)

The surrender of the Sikh Army

The excuse for a full annexation of Sikh territory was a minor insurrection in the remote province of Multan in 1848.

The British described it as a Sikh rebellion, giving them the excuse to take what remained of the independent Sikh state. In spite of a decade of incompetent, extravagant and fractious rule by Ranjit Singh’s successors, the Sikh army still put up one of the hardest fights the British ever encountered.

The major battle of the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49) was fought at Chillianwala on 13 January 1849. The British forces suffered the worst reversal ever to take place in their history of empire-building in the subcontinent. Despite ferocious resistance, the Sikhs were finally defeated at Gujarat.

In March 1849, after months of fighting, the army of the Sikh Empire laid down its arms at Rawalpindi. In Lahore, a fortnight later, a proclamation was read annexing the kingdom of Lahore to the British Crown. The dissolution of Sikh rule and the annexation of the empire signalled the last significant territory that the British would take possession of in the subcontinent.

British Raj in Punjab and Modern Times

The ferocity of the Anglo-Sikh Wars left an indelible mark on the British Empire.

The new rulers set about disarming the general populace whilst simultaneously recruiting locals for military service. As a result, Punjab became the major recruiting ground for Queen Victoria’s Indian Army. By the advent of the First World War (1914-18) nearly 20% of the army was Sikh, despite them comprising only 1% of the population of British India. They and other Indians would go on to serve again in even greater numbers during the Second World War (1939-45).

When the British withdrew from the subcontinent in 1947, Punjab was divided between Independent India and the Islamic Republic of West Pakistan. With the Sikhs’ demand for a homeland left unfulfilled, their leaders reluctantly chose to join India. In what would be the greatest mass exodus in human history, in which millions of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh refugees poured across the border, approximately a million lives were lost in communal massacres. With Lahore going to Pakistan and Amritsar to India, communities that had coexisted in relative peace for generations were torn apart.

Within two decades of the Partition, the Indian Punjab was further divided into three states, giving rise to the Sikh-dominated state of Punjab today.

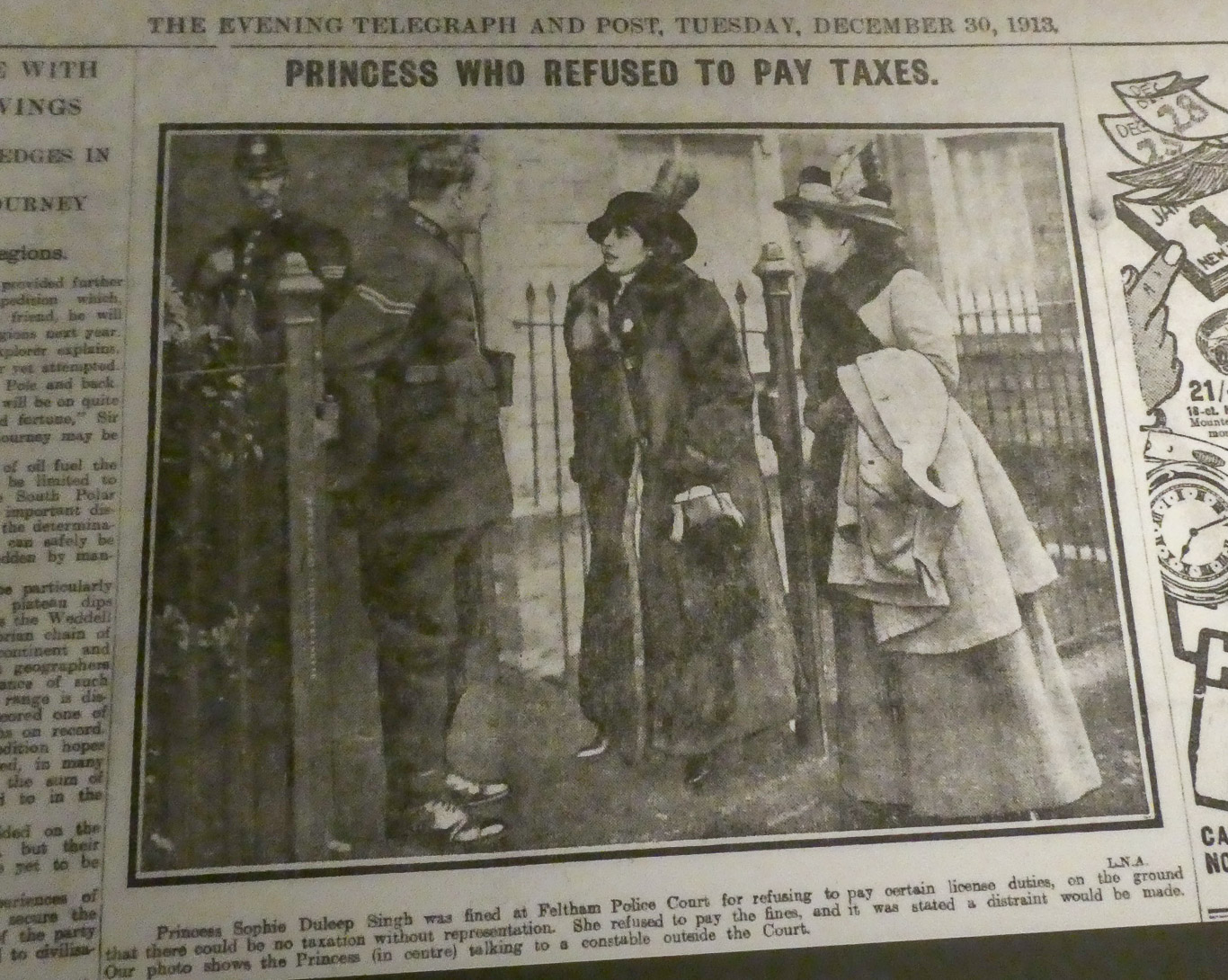

‘Princess Who Refused To Pay Taxes’

Princess Sophia (1876-1948) was the youngest daughter of Maharaja Duleep Singh and Maharani Bamber Müller.

When Sophie was 17, her father died a broken man in a Paris hotel. During the next few years, Sophia lived part of the time in Hampton Court in a ‘grace and favour’ house given by her god-mother, Queen Victoria. She and her sisters, Catherine and Bamba, enjoyed the leisured life of high society ladies. In 1907, she went to India for the first time with Bamba, visiting Amritsar and Lahore, once capital of her grandfather Ranjit Singh’s empire. Imbibing her father’s rebellious spirit, Sophia returned to become a ‘Votes for Women’ campaigner in pre-Great War England. As a prominent activist in the Women’s Social and Political Union, she marched to parliament alongside Emmeline Pankhurst at the head of the suffragette’s ‘Black Friday’ deputation in 1910. Witnessing over 150 women being physically assaulted but the police made Sophia even more determined to fight on. Risking her reputation in society to be at the forefront of campaigns to publicise women’s political rights, she joined the Women’s Tax Resistance League. In 1911, she was fined £3 for refusing to pay licences for her five dogs, carriage and manservant, declaring that ‘Taxation without representation is a tyranny’. In December 1913, following another case of non-payment of licence duties, Sophia was back in court (see newspaper cutting). A pearl necklace and a gold bangle studded with pearls and diamonds were seized and auctioned, only to be bought back again by sympathisers amidst a great deal of publicity. During the Great War, Sophia joined the Women’s War Work procession organised by Mrs Pankhurst. The women were calling upon the trades unions, amongst others, to let women work in the industries that had traditionally only allowed men. Sophia spent a great deal of time visiting the Indian troops in the hospitals on the south coast, as well as working as a nurse herself. Her visits were greatly appreciated, especially by the Sikh soldiers as they knew her as the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and were honoured by her interest in their plight.

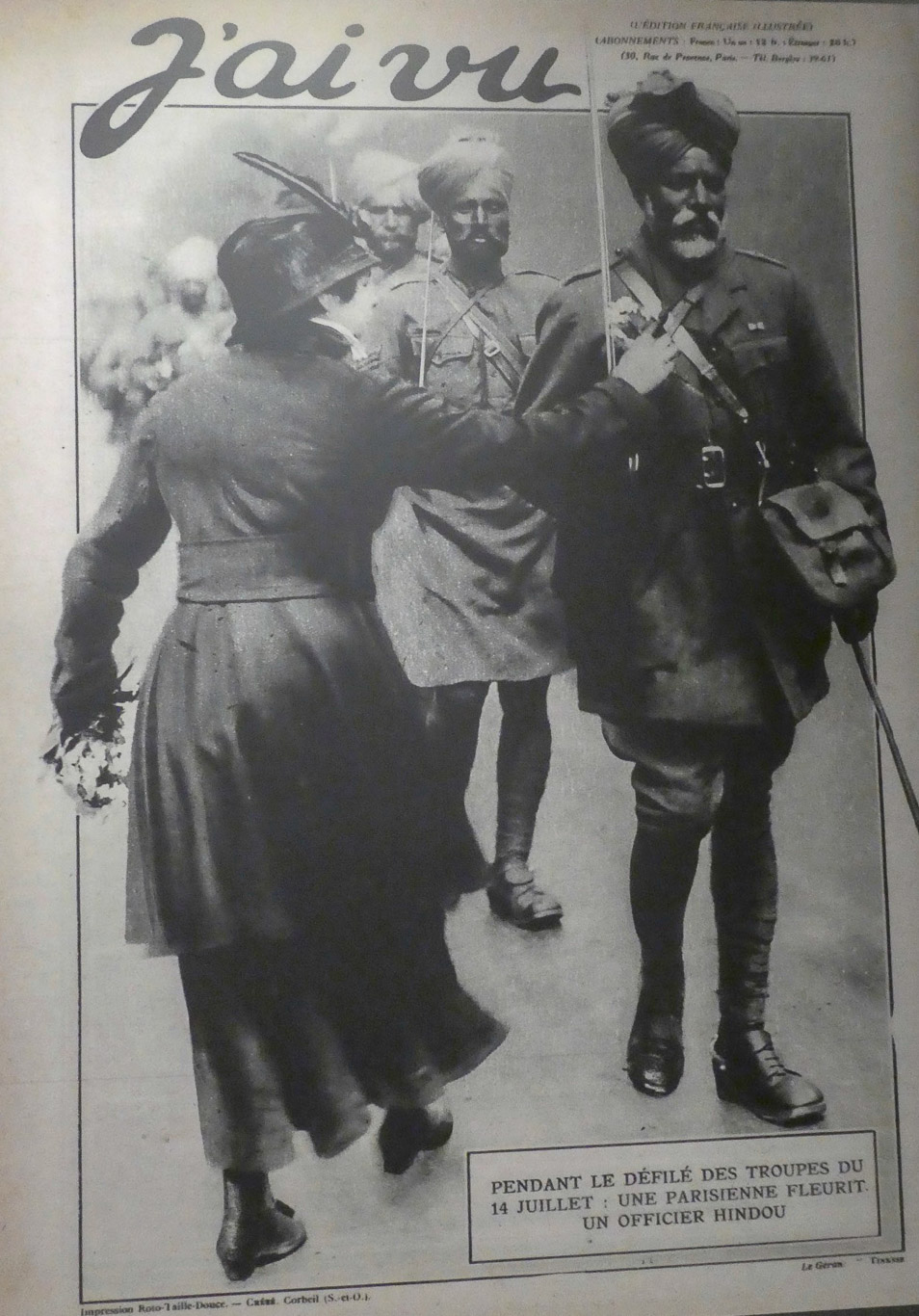

Sikh troops receive a heroes’ welcome in France

A French lady pins flowers onto the tunic of a soldier marching through Paris on Bastille Day, 14 July 1916.

When the Sikh Empire collapsed in 1849, the gifts and letters of friendship exchanged between the royal courts of Lahore and Paris abruptly ended. The advent of the Great War gave Sikhs an opportunity to renew that relationship. Many Sikh soldiers wrote home in praise of their hosts.

Partition of Punjab

The birth pangs of the republic of India and the Islamic republic of West Pakistan culminated in unprecedented bloodshed.

For a community that had, two centuries earlier, forged its own powerful empire stretching from the Khyber Pass across the vast plains of Punjab to the borders of Tibet, and almost as far south as Delhi – which had briefly submitted to the Sikhs in 1783 – the formation of the two new nations in 1947 was a particularly difficult episode. With the partitioning of its traditional homeland of Punjab, the Land of Five Rivers, families were torn apart from their kith and kin, and uprooted from their ancestral homes and the lands they had tilled for generations. Another bitter blow for the Sikh community was the loss of access to over 130 historic gurdwaras in Pakistan, including one marking the birthplace of Guru Nanak.

Victorian Encounters

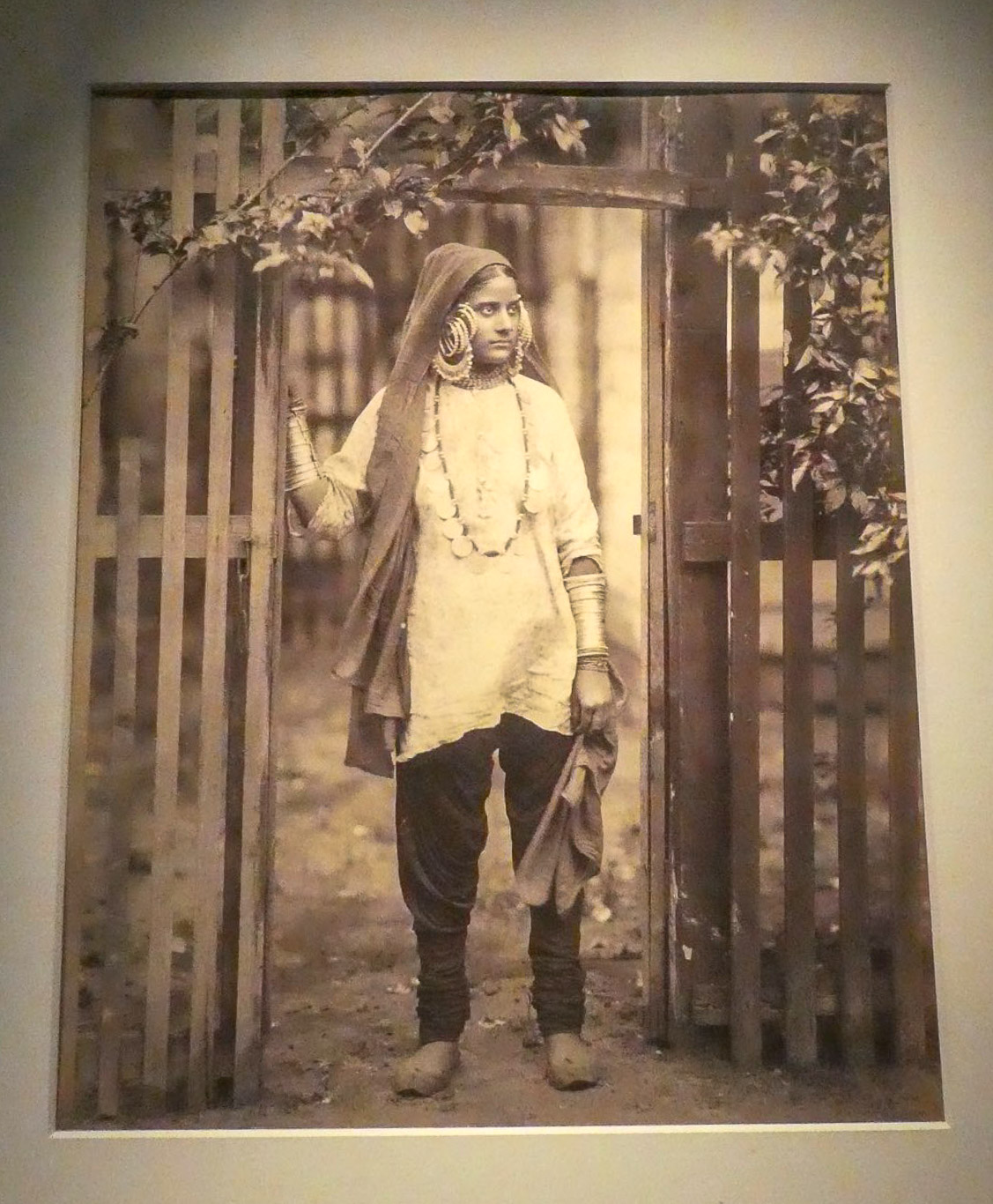

A Sikh woman

19th century photographs of Sikh women are extremely rare.

Weavers and spinners at work creating Kashmir shawls

Kashmir shawls were woven from the finest hairs of the Tibetan shawl-goat, extremely prized, giving rise to a huge export industry. Under Sikh rule Amritsar and Lahore became great centres of the shawl trade, employing tens of thousands of people. Making intricately patterned shawls often took up several years of a weaver’s life.

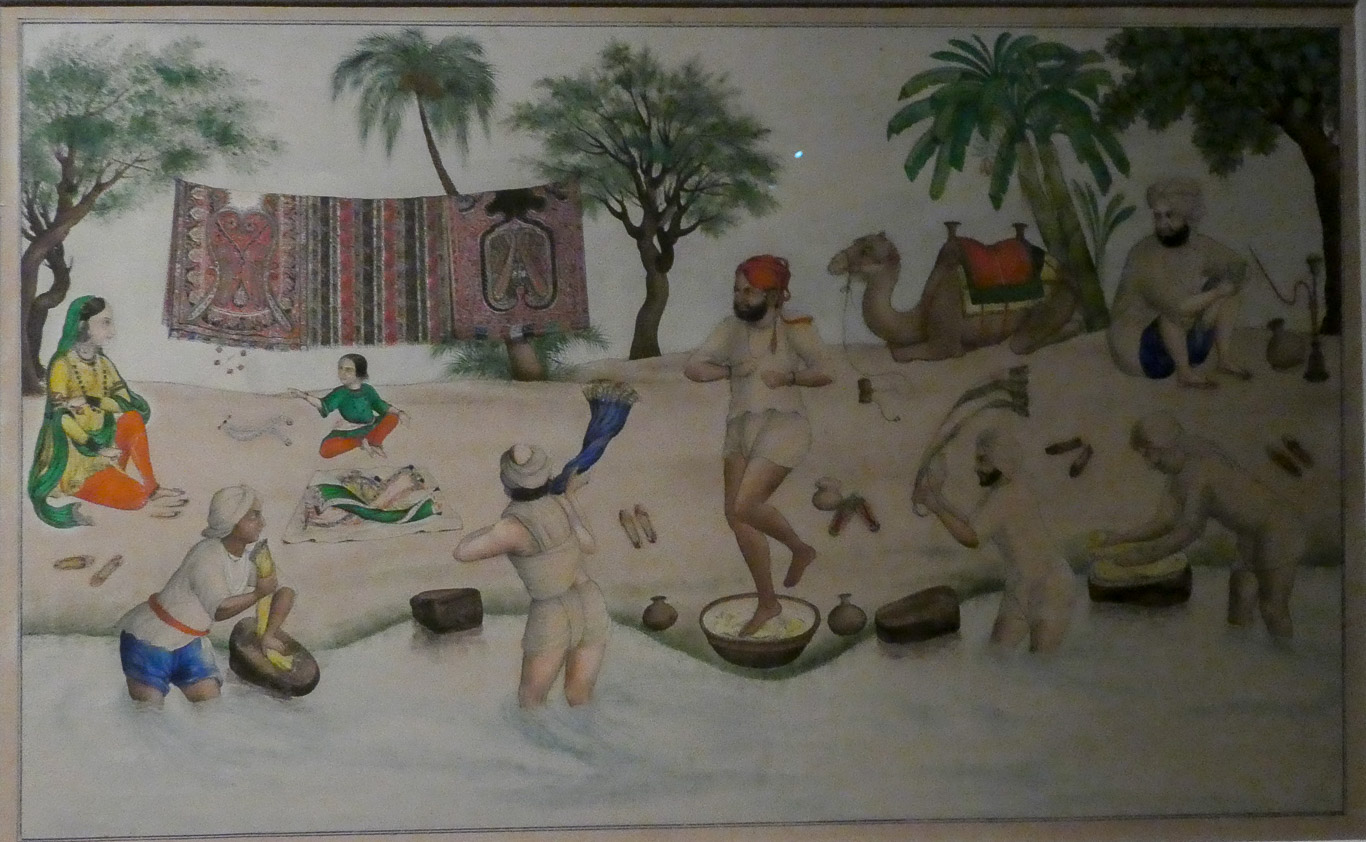

Washing Kashmir shawls on a river bank

The river here is probably the River Jhelum in Srinagar, in the heart of the Kashmir valley. Shawl operatives believed that the waters of the Jhelum held special properties that accounted for the superiority of Srinagar shawls to those made elsewhere.

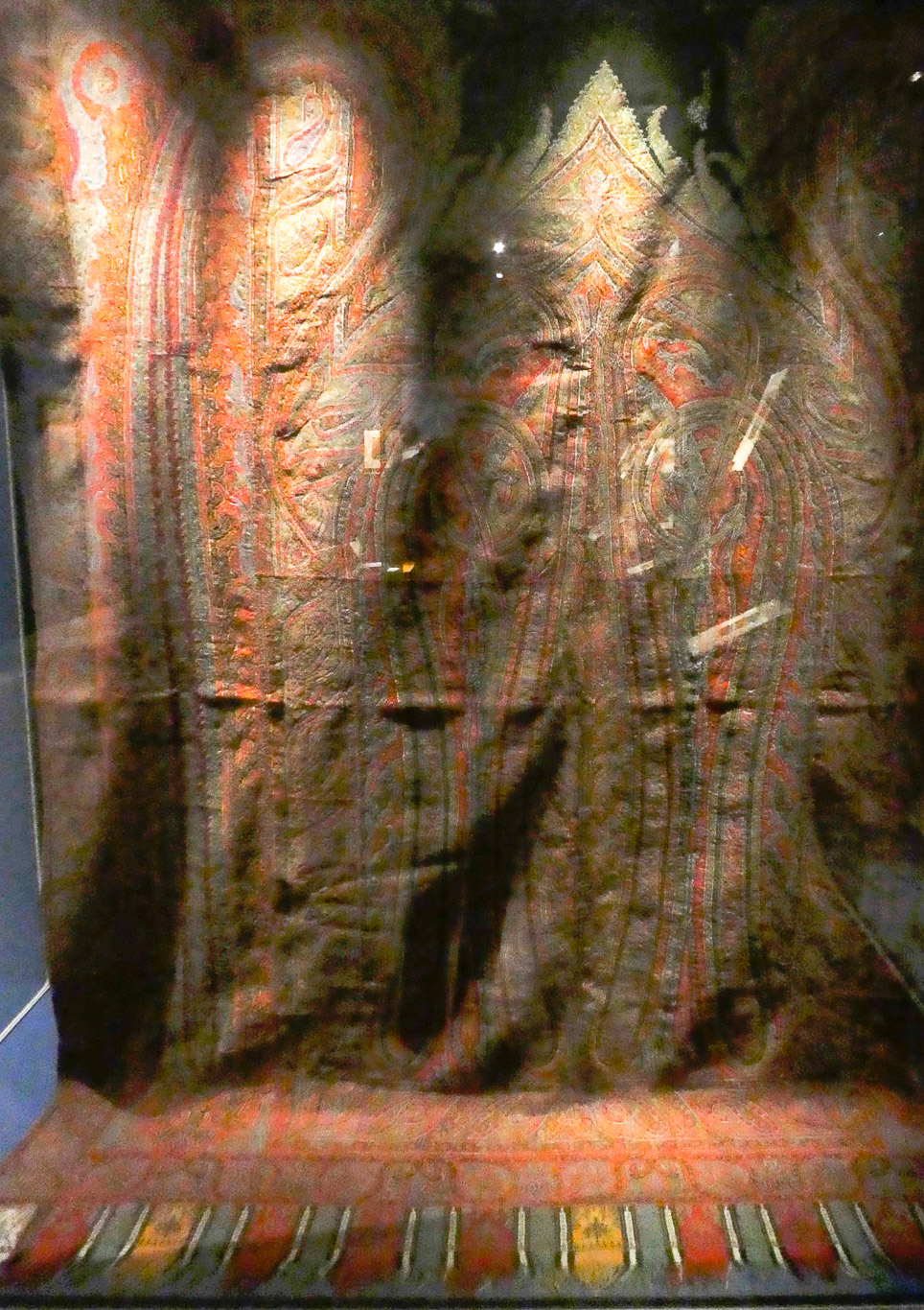

Kashmir shawl

The intertwining curves of the paisley design combine to show the complexity of great shawls from this period. Such sumptuous textiles were often exchanged as luxurious gifts in royal courts across the Indian subcontinent.

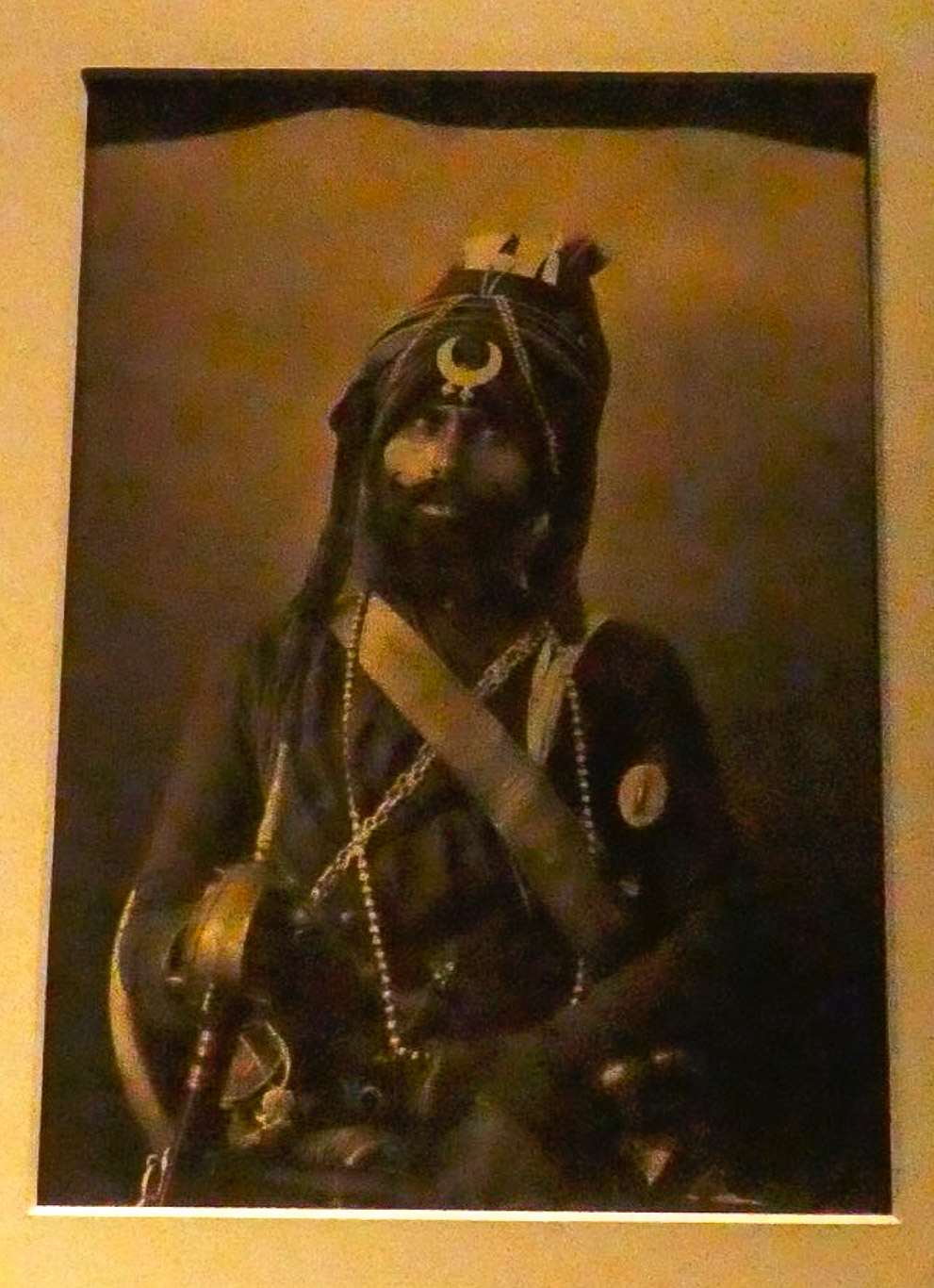

A Nihang bodyguard serving in the Nizam of Hyderabad’s irregular Sikh army.

Traditionally the most fearsome Sikh warriors were styled ‘Nihang’, which is Persian for crocodile. This impressively armed Nihang Sikh has fortified his battle-turban with an array of razor-sharp steel weaponry including quoits and miniature daggers.

A Nihang with a conspicuous tall turban

This portrait was taken as a part of a series illustrating the different types of head-dress work in British India. It’s most striking aspect is the grand steel emblem called gaigah (elephant ornament) bound to this Nihang Sikh’s peaked dastar bunga turban. Sikh tradition has it that in only ancient times, only those warriors who had proved themselves in battle could wear this emblem.

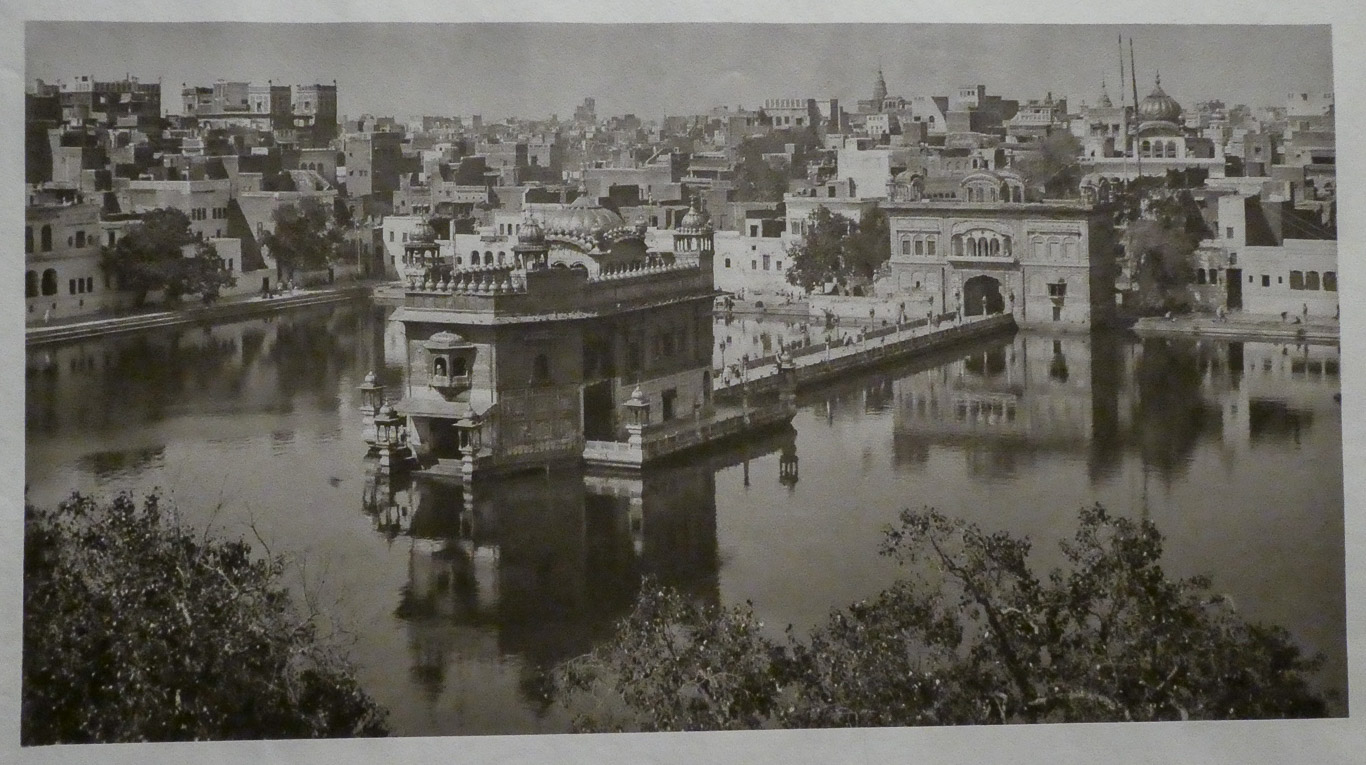

View of the Golden Temple and the city of Amritsar

Taken by Herbert Ponting who, ten years later, became the photographer for Captain Scott’s Antarctic expedition of 1910-13.

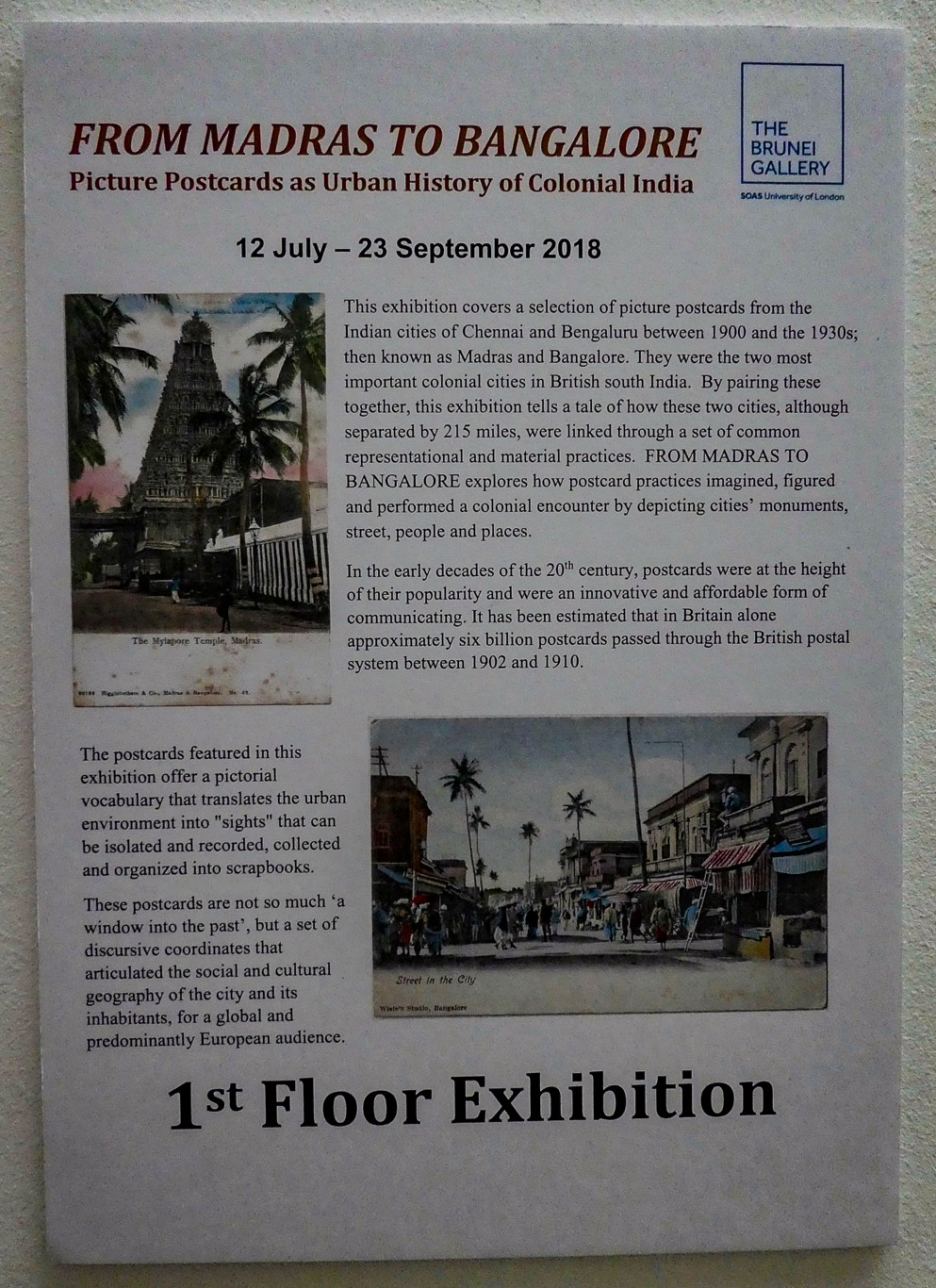

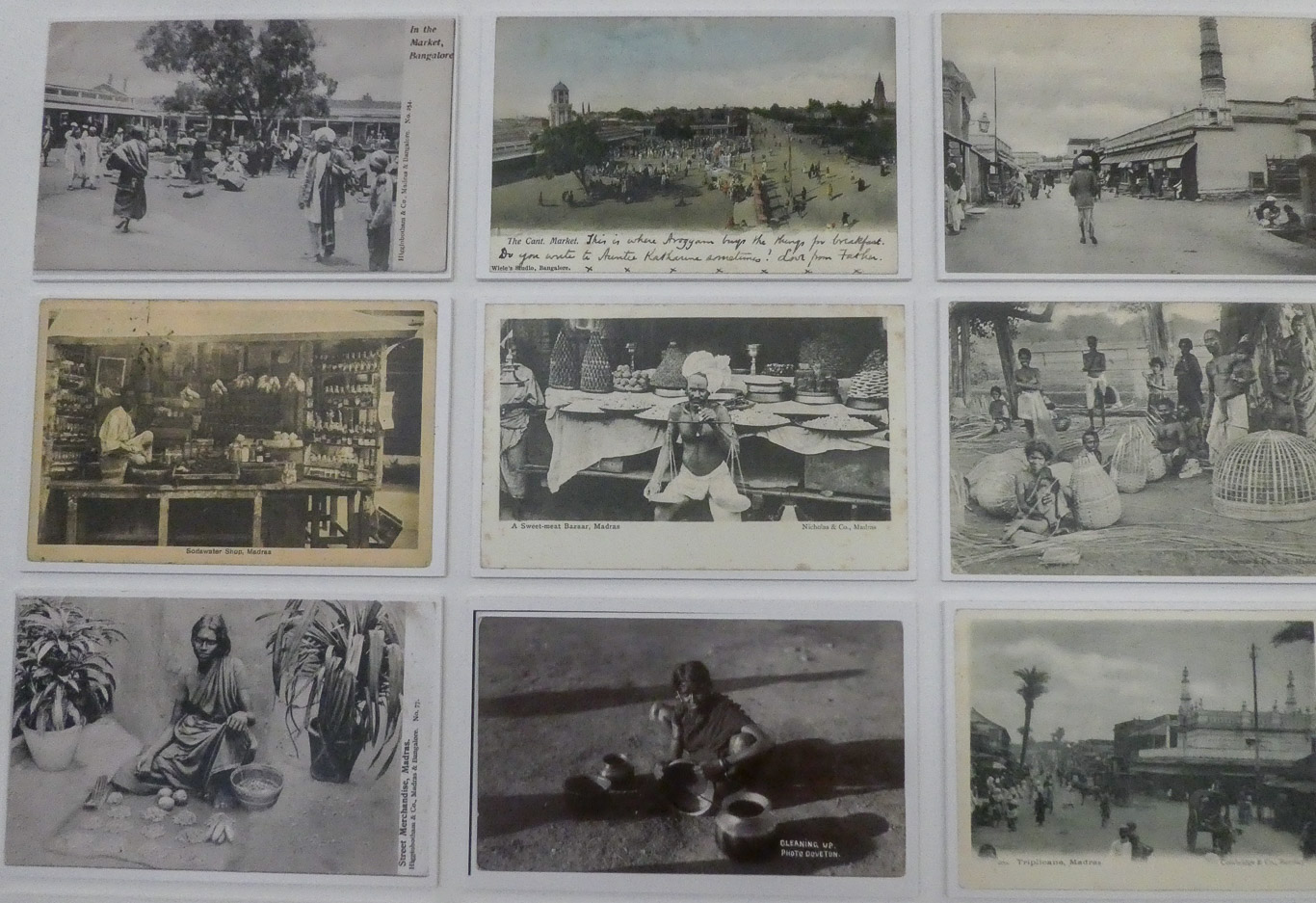

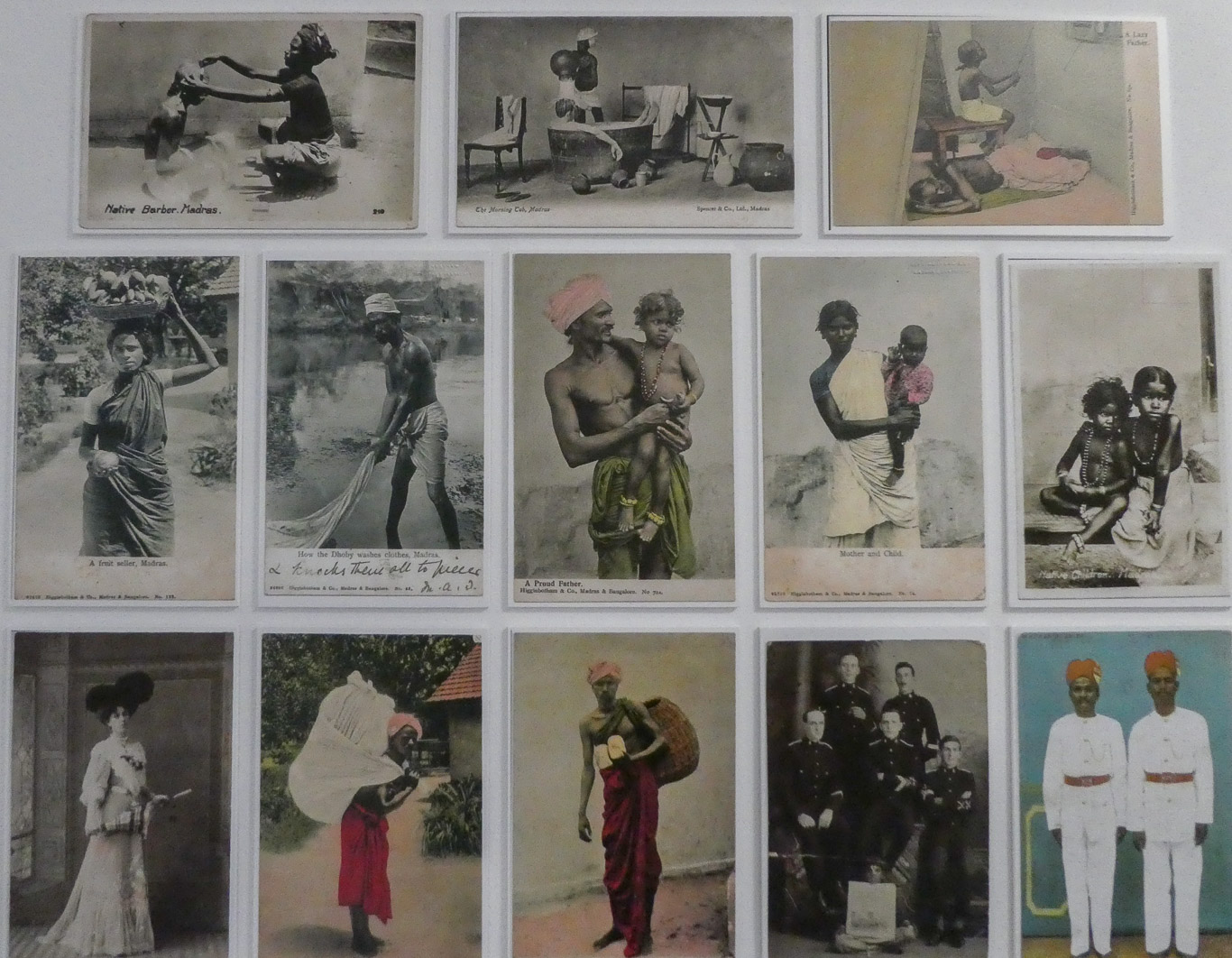

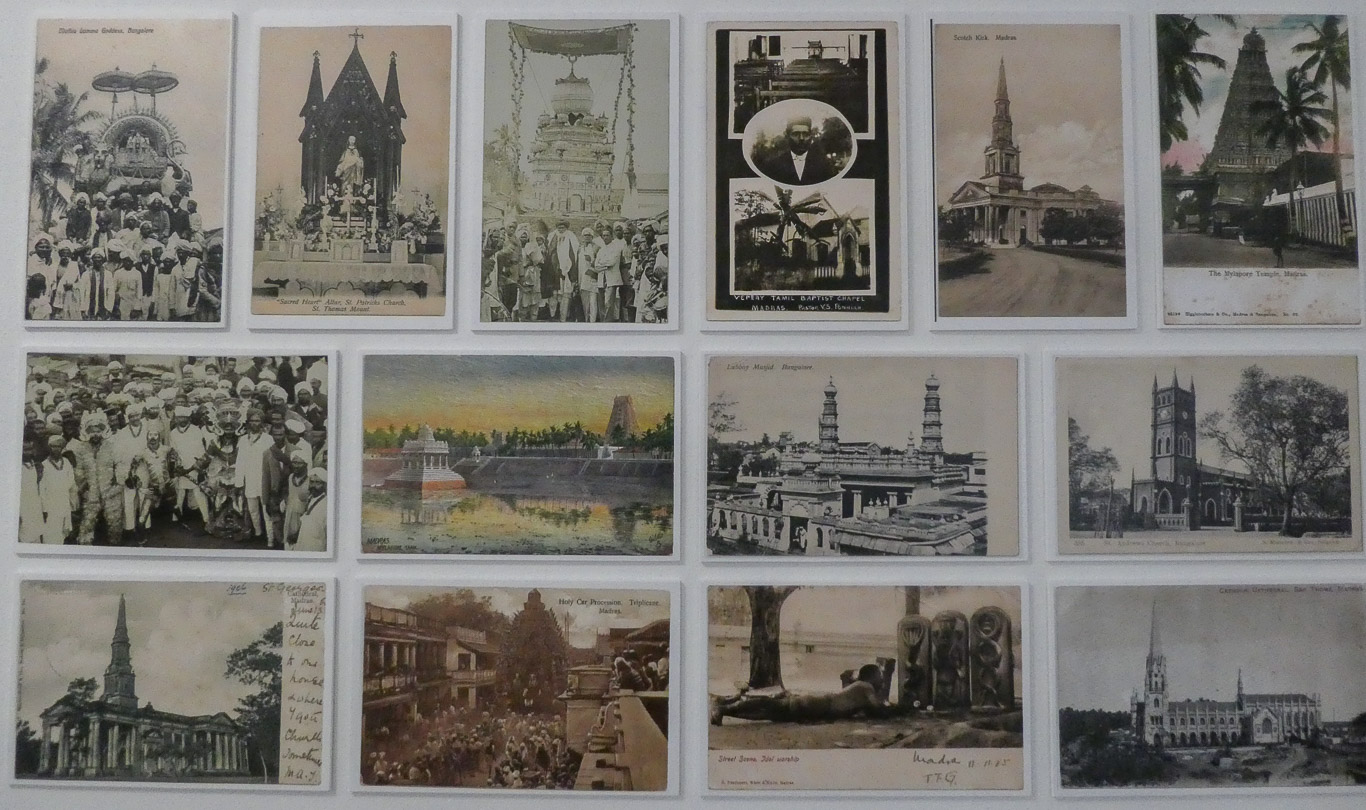

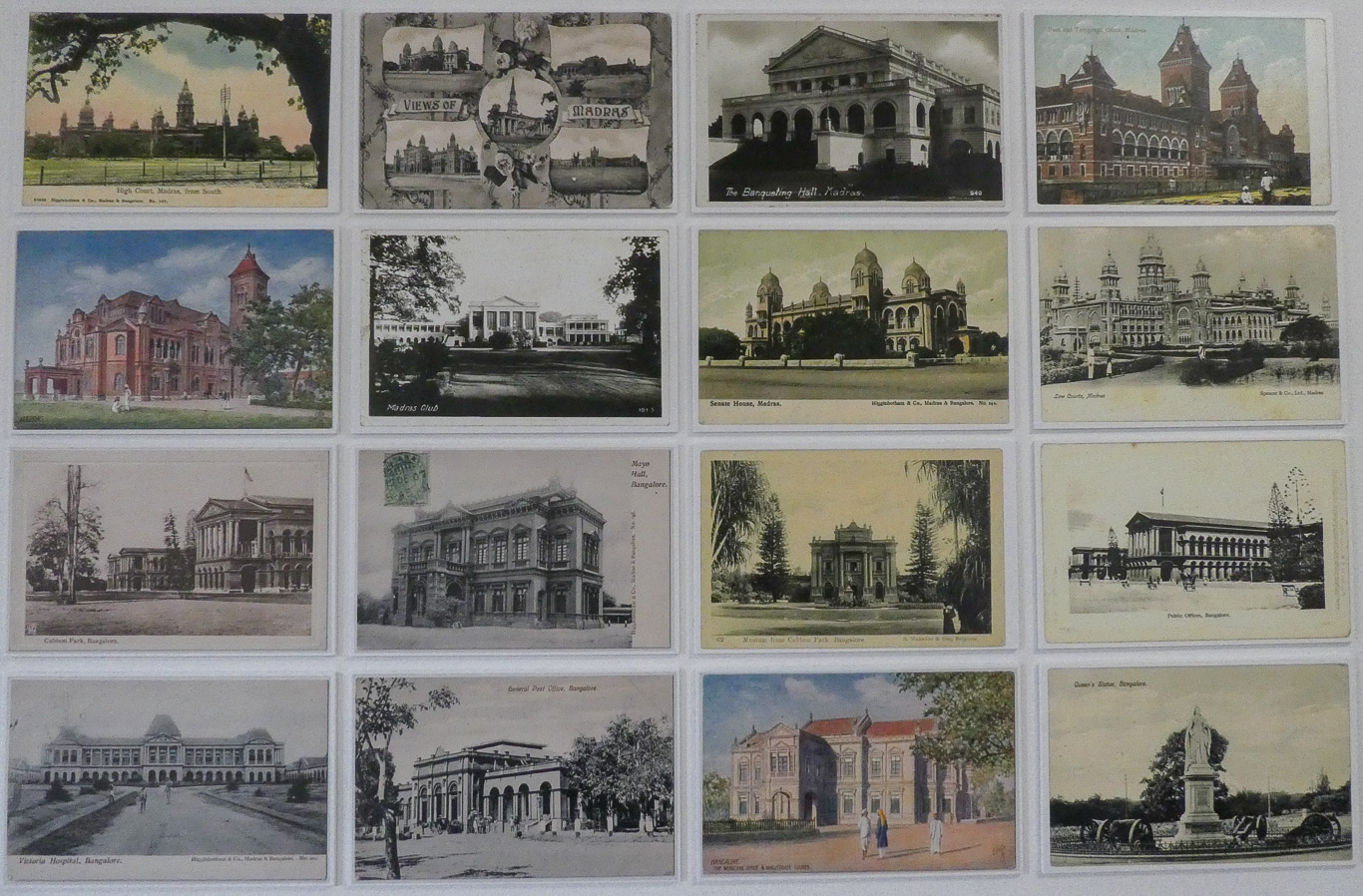

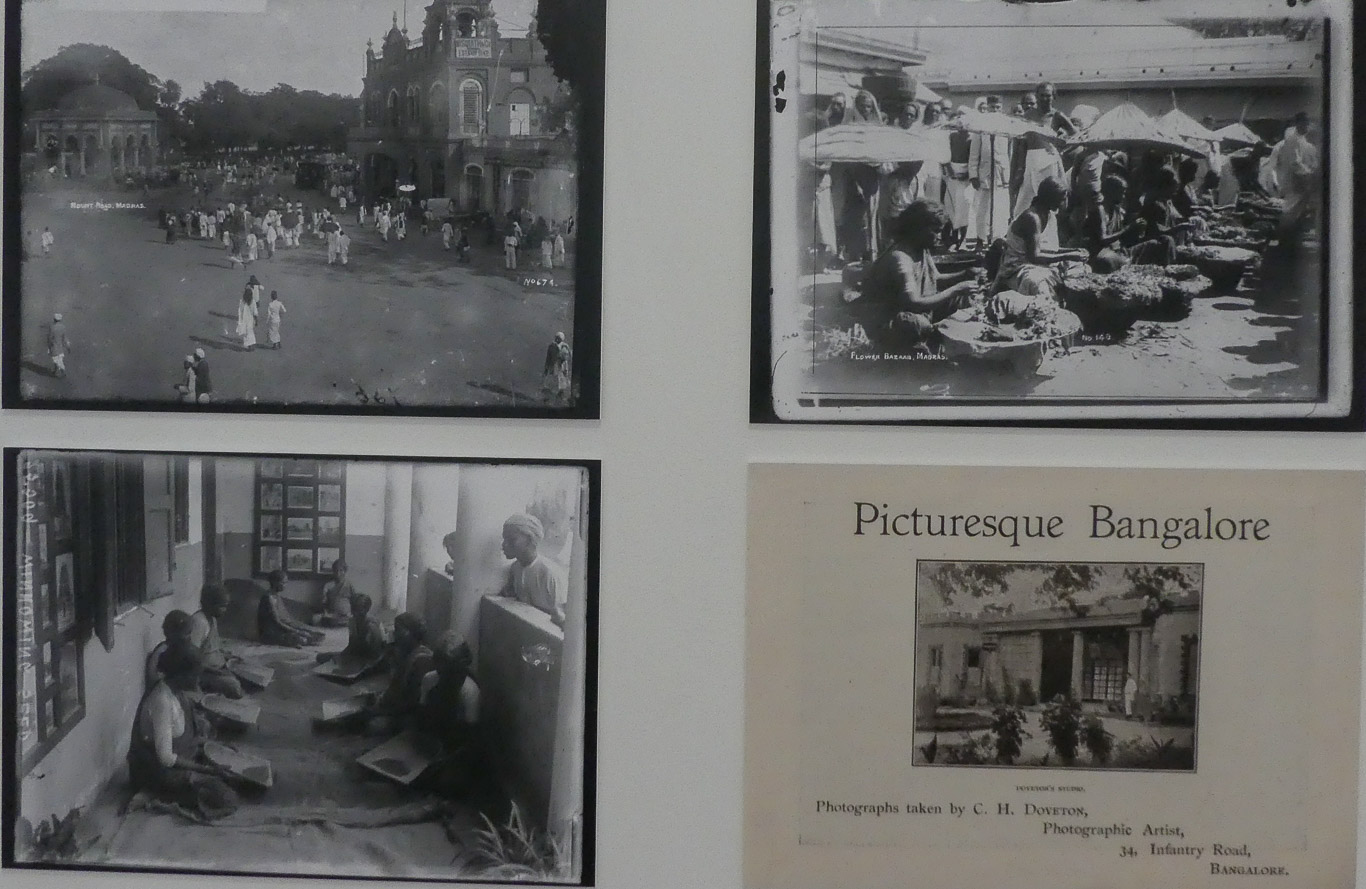

The postcard collections (in first floor exhibition) – gives a more intimate experience of colonial India.

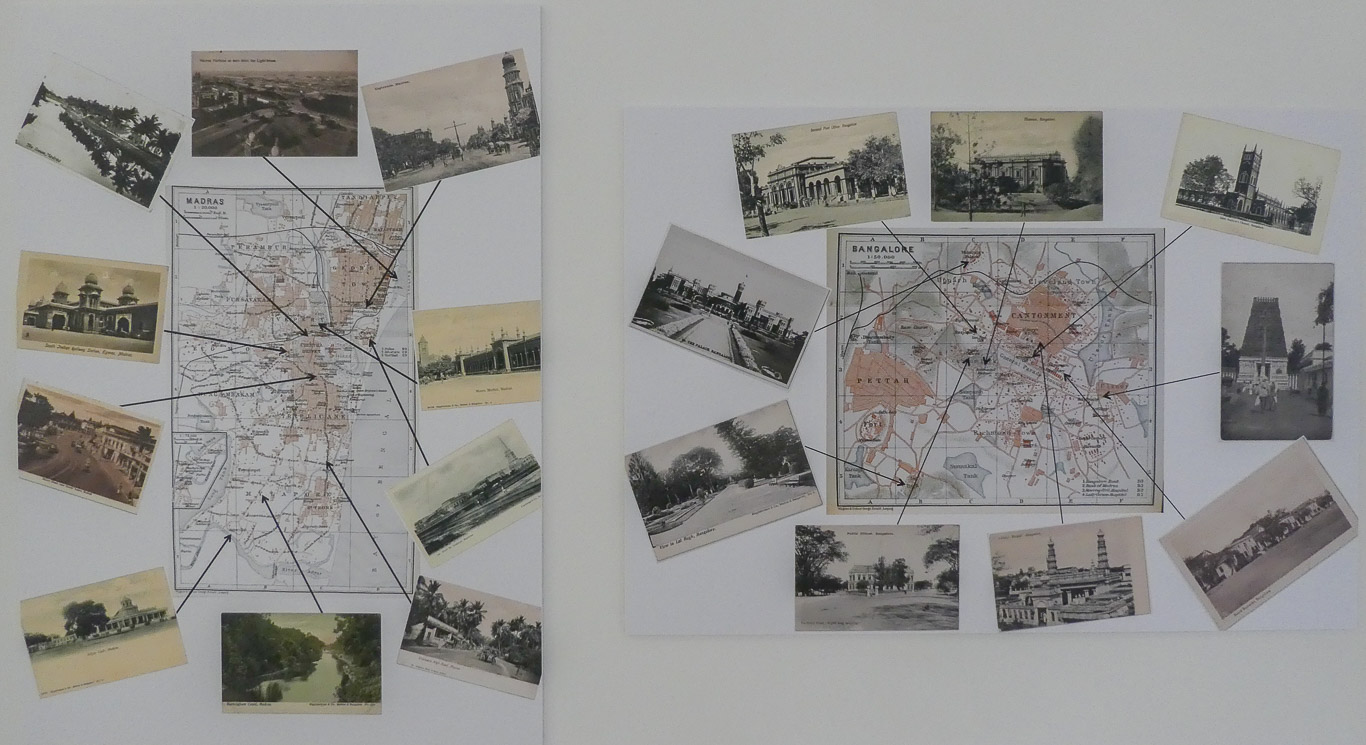

I found the postcard collection incredibly interesting especially when you think of how modern they were at the time. The exhibition covers a selection of picture postcards between 1900 and the 1930s from the cities of Chennai (Madras) and Bengaluru (Bangalore) 215 miles away, which were the two most important colonial cities in British south India at this time.

Why old postcards?

Postcards were the first widely available and affordable form of mass produced photography. In the early decades of the 20th century, when postcards were at the height of their popularity, they were a new media craze that swept the globe. They were something akin to the Instagram of this century, an innovative and affordable mobile form of photo sharing and social networking. It has been estimated that in Britain alone approximately six billion postcards passed through the British postal system between 1902 and 1910.

Though Indians were often involved in producing, photographing and selling postcards featured in this exhibition, the cards were addressing a predominantly European market of residents, travellers and foreign collectors. There can be no doubt that the postcards of Madras and Bangalore spoke in the main to European expectations, perspectives and experience of the cities. Yet as the Indian people in these images look directly at us through the photographer’s lens, it is clear that they still have their own stories to tell from the past.

Chennai /Madras

Chennai formally known as Madras until being renamed in 1996 serves as the capital of the southern state of Tamil Nadu and was the first British port city in colonial India. In 1639 the English East India Company acquired a sandy strip of what was then wasteland along the coast from local rulers. This was the first territorial possession in India by the English which let to it being called the ‘birthplace of British India’ The city served as the administrative, military, industrial, mercantile, banking and educational centre for a large part of British southern India. In the late 19th century Madras’ European population was small and dwindling yet it remained disproportionately wealthy and powerful as a group. Europeans dominated almost every aspect of political, economic and social life in Madras during the pre-independence period. Europeans had exclusive control of the government, the port, shipping and railways and had a near monopoly in foreign trade and banks.

Bengaluru /Bangalore

Bengalaru formally known as Bangalore until being renamed in 2014, is the capital of the Indian state of Kamataka and in the 19th century was thought of as the ‘Garden City’ due to its temperate climate, abundant greenery and small population. Bangalore was physically, administratively, culturally, linguistically and economically divided between the pre-colonial city and the British military outpost (cantonment) established in 1809 after the British East India Company defeated the ruler of Mysore in 1799. The British military outpost quickly expanded to become a kind of European enclave where the majority of Europeans lived with open spaces, strict zoning regulations and large, enclosed bungalow compounds and colonial descriptions of the area beyond the cantonment was seen as over-populated, unsanitary and disorderly with the British limiting contact between the city and the cantonment as far as possible. Being a smaller city located in-land, Bangalore relied on Madras as the nearest port city. In 1864 the two were connected via rail, allowing for the faster movement of people and goods. The two cities were consequently deeply connected yet quite different colonial cities.

In the streets of Madras and Bangalore

Numerous postcards of streets show commercial life represented by shop fronts and people going about their daily shopping or work, many of them staged.

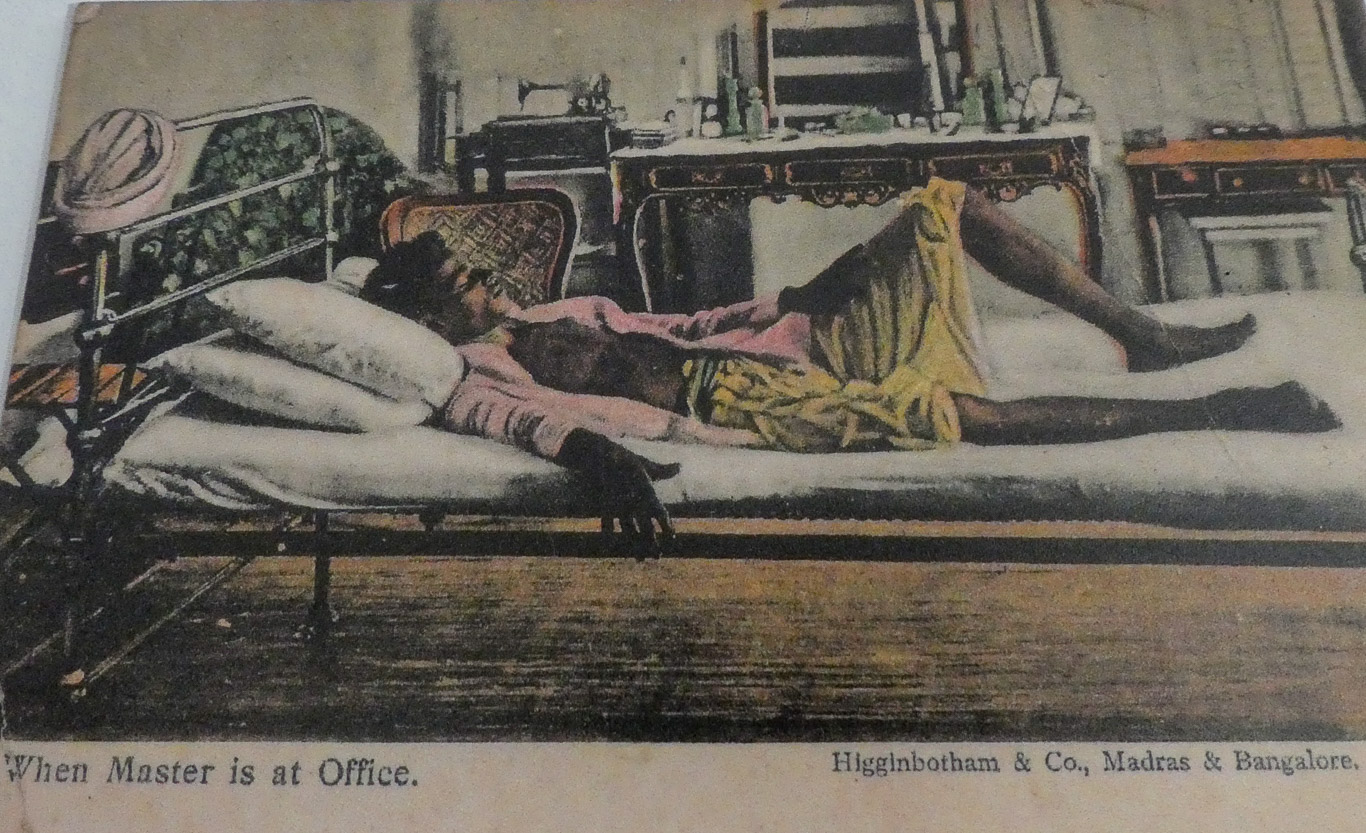

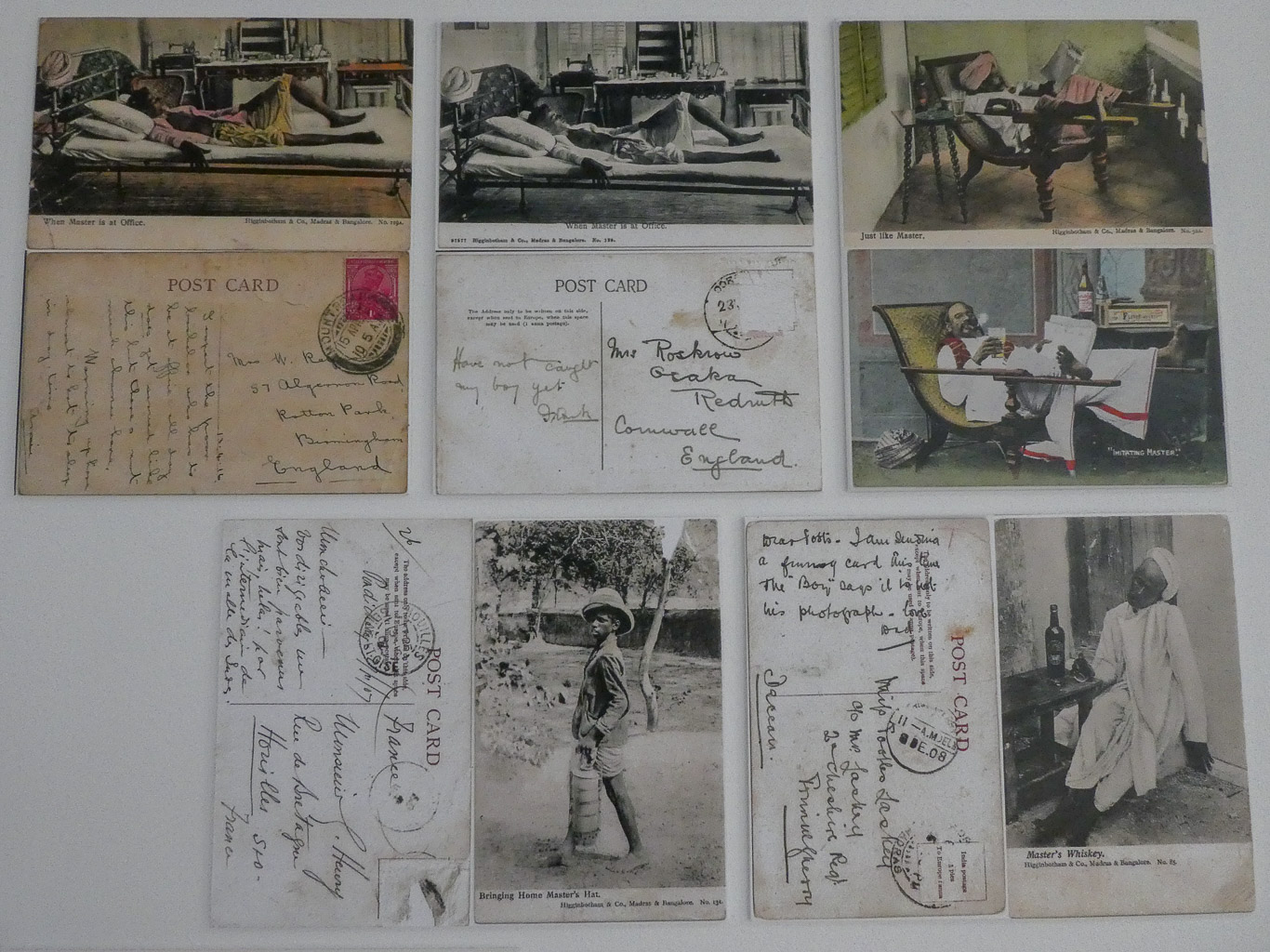

The ‘Master’s’ series of postcards

A leading bookshop in Madras and Bangalore brought out series of postcards poking fun at the master/servant relationships at the heart of British life in India; staged scenes where the servants mimicked their ‘masters’ and suggesting insubordination and subversion of the presumed hierarchy. The postcards played on British insecurities and anxieties about what their servants were up to when not supervised.

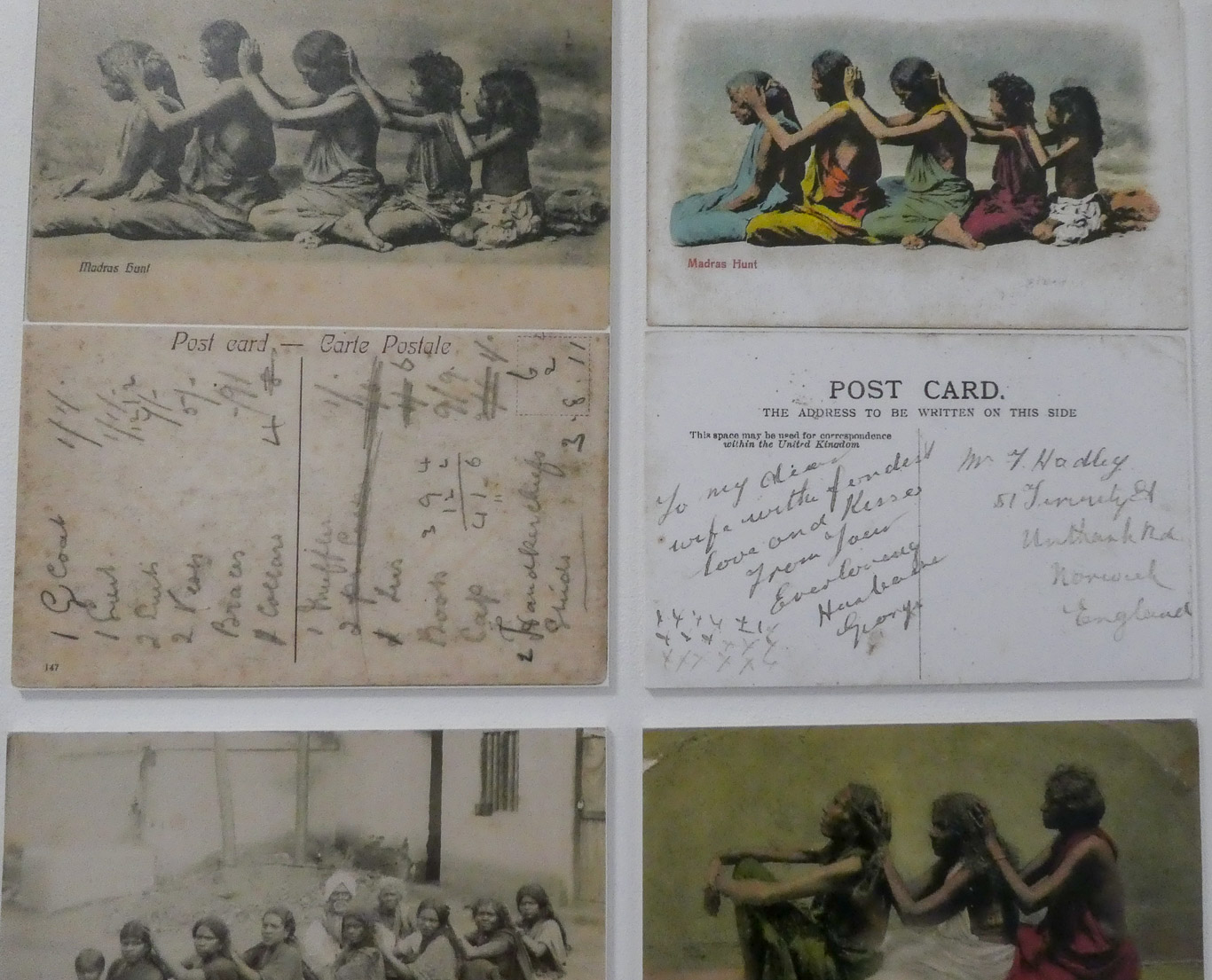

The ‘Madras Hunt’ series of postcards

This series of images depicting a line of women and children in such a manner as to invite the viewer to imagine they were delousing one another. One of the first things one notices about these postcards is the careful staging that went into posing these scenes. In several of the images it is obvious that they are in a studio against a painted backdrop. Someone was directing the action in the photograph and the women were performing their roles. The caption ‘Madras Hunt’ was a kind of visual pun with the Indian women hunting for lice and the British male sport of hunting that had strong and popular associations with colonial rule in India. This series is provocative and demeaning, but highlights attitudes of the time being one of the most commercially successful series sold and posted in Madras and Bangalore in the first decades of the 20th century. They were printed in Germany, Italy and England and had a circulation that went well beyond south India.

Postcards of people

There were also postcards of the Indian inhabitants of Madras and Bangalore though not as individuals but rather identifying them by their ethnicity, gender, religion or caste but most often by their means of employment. The postcards of these people encouraged the idea of Indians as subordinate to Europeans, under colonial rule. In contrast, the Europeans living in these areas were rarely pictures unless being served or relaxing in public spaces.

Religious life

There were postcards of places often religious buildings though from a predominantly European perspective. Most common of all cards on religious themes were those depicting Christian churches with their imposingly large edifices emphasising their importance in colonial social life and often with only an occasional figure or animal added for perspective. In contrast to the Christian themed postcards, Hindu add Muslim religious practices were often shown as crowded and busy affairs.

Visualising power: monuments, public buildings and statues

Major architectural projects were used in colonial India to project the power, achievements, benefits and glories of British rule.

To Mr and Mrs McDonald: Postcards from India to Scotland

This panel is based on a collection of postcards sent between 1904 and 1912 that were sent between India and Scotland. The collection included nearly two hundred postcards of various Indian cities especially Madras and Bangalore. The postcards were primarily send by Mr and Mrs Brown to Mr and Mrs McDonald in Edinburgh, they therefore give us a glimpse into the lives of both families and show how they maintained their connection whilst separated by thousands of miles.

The postcards show that the Brown family lived in Madras with their daughter Ella and giving details of their daily life. The collection show the close connections between Europeans living in Madras and Bangalore. The Browns visited Bangalore for holidays because of its more temperate climate.

Annie’s postcards / May’s album

Postcards were treasured objects that were valued and collected. Albums were a common format for organising and displaying such collections. The album on display here contains 120 postcards compiled by the teenager May Reynolds in Birmingham. The postcards date between 1912 to 1919 and all but a small number were written by her aunt, Annie Reynolds who moved to Madras in 1912 to join her husband Will who worked in the office of an automobile business run by his uncle. The messages tell the story of Annie and Will’s everyday life in Madras with local landmarks pointed out. The postcards were also written to show their holiday travels in south India to Bangalore, the Niligiri Mountains and to Mahabalipuram.

A fascinating exhibition, I wish we had had more time to look at all the exhibits!